Language: Mandarin Chinese

Source: Period texts

Description

Wōdāo, written both 倭刀 and 窩刀, literally means "Japanese (style) saber".

In most sources, the wōdāo is classified as being about 120 cm long.

Both names refer to the Japanese pirates that frequently raided coastal China during the Ming dynasty, called wōkòu (倭寇). Wō (倭) means "Japanese" or "dwarf", kòu (寇) means bandit, and wō (窩) can be translated as "a bandit's lair".

A Chinese long saber.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2017.

A Qing dynasty long saber with some Japanese design elements.

Author's collection.

The example above still has a number of Japanese features:

-Blade with ridged cross-section as common on Japanese swords.

-Tsuba-style guard, with even small hole emulating the hitsu-ana on Japanese tsuba.

-A wrap with crossings, and no center loop.

Adoption in the Ming dynasty

The Japanese pirates, wōkòu, consisted of a mix of Chinese and Japanese troops and were among others equipped with long Japanese two-handed sabers called ōdachi (大太刀). Notable Ming general Qi Jiguang (戚繼光) started to adopt these sabers into the Ming military and successfully managed to fight off the pirates.1

The Japanese-styled long saber was to stay in the Chinese arsenal long after these clashes. During the Ming dynasty, the large two-handed sabers were usually referred to as dāndāo (單刀) "single saber", referring to their method of use or chángdāo (長刀) "long saber", although wōdāo (倭刀) also remained in use.2

Wōdāo in the Qing dynasty

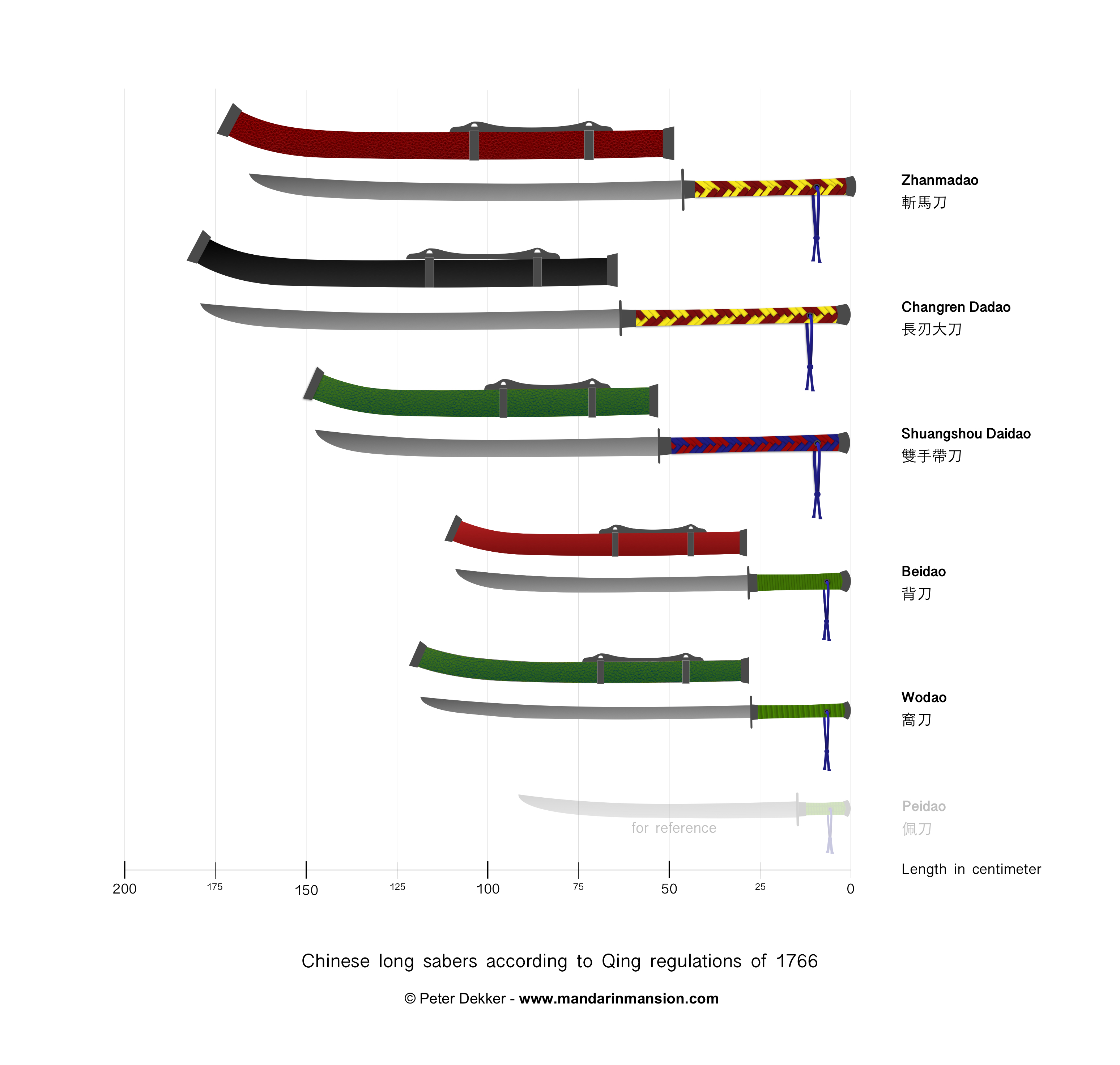

By the mid-Qing dynasty, seven distinct types of long sabers had evolved. This is also the first time we see 倭 sometimes replaced for 窩 in the name. For all seven, see my article Chinese long sabers of the Qing dynasty.

Below a diagram, showing that it was by no means the largest anymore at this point in time:

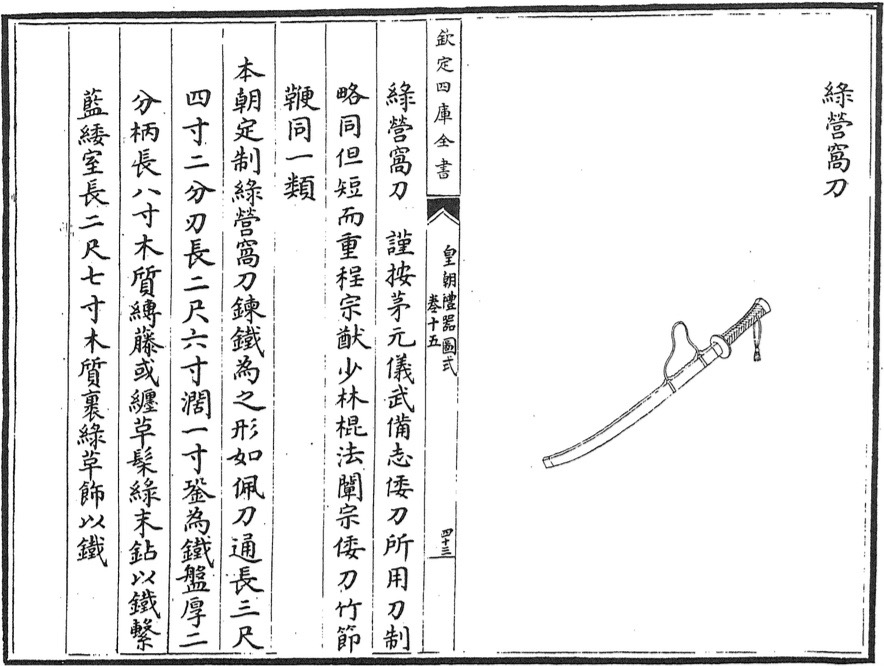

See below a page from the mid 18th century regulations concerning the wōdāo:3

Illustration of a wōdāo in the 1766 woodblock edition of the Huangchao Liqi Tushi.

My translation:

"According to Mao Yuanyi’s BOOK OF MILITARY PREPAREDNESS:

“Japanese swords: The ones they use can be summarized as being quite alike, short and heavy.” 1

Cheng Zongyou’s EXPLANATION OF SHAOLIN STAFF METHODS:

“Japanese swords, bamboo sectioned whips, they are the same.” 2

The regulations of our dynasty:

Made of forged iron [as to produce steel], it is shaped like a peidao.

Overall 3 chi 4 cun and 2 fen long. (Approx. 120 cm / 47 inch) 2

The blade is 2 chi 6 cun. It is 1 cun wide.

It has an iron disc guard that is 2 fen thick.

The handle is 8 cun and made of wood. It is either wrapped with rattan or in braided wrap with [strips of] leather, lacquered green. Iron pommel. It has a blue lanyard.

The scabbard is 2 chi 7 cun long, made of wood that is covered with green leather. It has iron fittings."

Notes to translation

1.This particular quote clearly concerns the katana, not the ōdachi.

2. A bamboo-sectioned whip is a very heavy striking weapon. Cheng Zong You is referring to the heavy striking power of the Japanese sword here.

3.This is about the size of the crossbowman's long saber described in Cheng Zong You's manual.

By the Jiaqing period, only five long sabers remained in use (1796-1820). A text meant for the imperial workshops discusses the weapon in more detail than above, and among others states that the finished blade weighs just over a kilo, is 7mm thick and 35mm wide.4

By the Guangxu period (1875-1908) the wōdāo is the only long saber that remained in use.5

Republican period

In the decades after the fall of the Qing, Chinese martial arts saw somewhat of a revival under the name guóshù (國術), literally meaning "national arts". On the curriculum was the Chinese long saber. Dān jiè dāo (單戒刀) or "Single defence saber" by Jīn Yīmíng (金一明) published in 1932 also mentions the the wōdāo among a list of swords in use at the time.6

The wōdāo entry:

倭刀(即雙手舞之長苗刀)

Wōdāo (jí shuāng shǒu wǔ zhī cháng miáodāo)

Translated:

"Japanese [style] sword (which is a double handed long miáodāo)"

Wōdāo to miáodāo

It is understandable that the Chinese, with a renewed interest in their own fighting arts, sought to disassociate their long saber with the Japanese.

Interestingly, this went both ways. Around the same time, the Japanese changed the name of their national fighting art, karate, from 唐手 "Chinese hand" to 空手 "empty hand", sweeping its Chinese origins under the rug.7

The word miáo in miáodāo referred to the slender and gently curved shape of the blade, which is similar to a rice sprout.

Rice sprouts, and their resemblance to these sabers.

So in early Republican period China, miáodāo -referring simply to the blade's shape- became a more politically correct name and ultimately survived into modern times.

Addendum: earlier Japanese influence on Chinese swords

Chinese and Japanese sword makers have long influenced each other. It were initially a number of Chinese swords and sword makers that kickstarted the Japanese sword making tradition, some of these early swords dating from the Tang dynasty (618 - 907) are still preserved in the Japanese Shōsō-in (正倉院), an 8th century treasure house with artifacts made before 760 A.D.8

Ji Qiguang was also not the first to be inspired by Japanese bladesmithing early as 1380 A.D., Ming dynasty records speak of the manufacture of tens of thousands of wōgǔndāo (倭滾刀) or "Japanese rolling sabers".9 The gǔn in the name, meaning "rolling" probably refers to their intended use with the gǔnbèi (滾被) or "rolling blanket", a 6-7 cm thick blanket held up by skirmishers to stop incoming projectiles.10

Other Chinese sword names that refer to Japanese style swords are wōyāodāo (倭腰刀) or "Japanese waist saber", wōshì yāodāo (倭式腰刀) or "Japanese style waist saber", and fǎng wōdāo (仿倭刀) or "imitation Japanese swords".11

Further reading

For an interesting discourse on late Ming dynasty sword collection, see: Kathleen Ryor; Wen and Wu in Elite Cultural Practices during the Late Ming published as part of a series of essays in Military Culture in Imperial China, edited by Nicola Di Cosmo. Harvard University Press, 2011.

Notes

1. Mentions of the wōdāo appear among others in: Mao Yuanyi (compiler); Wǔbèi Zhì (武備志) or "Treatise of Military Preparedness". Finished in 1621. Yun Lu (允祿), et al, editors; Huangchao liqi tushi (皇朝禮器圖式) or "Illustrated Ceremonial Paraphernalia for our Dynasty", 1766 woodblock print edition, based on a 1759 manuscript. Chapter 15.

2. See among others Mao Yuanyi (compiler); Wǔbèi Zhì (武備志) and Cheng Zongyou's Dāndāo fǎ xuǎn (單刀法選).

3. Yun Lu (允祿), et al, editors; Huangchao liqi tushi (皇朝禮器圖式) or "Illustrated Ceremonial Paraphernalia for our Dynasty", 1766 woodblock print edition, based on a 1759 manuscript. Chapter 15.

4. Tojin (托津) & Cao Zhenyong (曹振镛) (compilers; Dà qīng huì diǎn tú (大清會典圖). Finished in 1818, covering the period of 1758-1818. Chapter 56. For the more detailed specs, see the incredibly rare text Qīndìng gōng bù jūn qì zé lì (欽定工部軍器則例) or "Imperially commissioned regulations and precedents on military equipment for the Board of Works". Published 1815.

5. Kungang (昆崗) & Xu Tong 徐桐 (compilers); Dà qīng huì diǎn tú (大清會典圖). Finished in 1899, covering the period of 1813-1887. Chapter 101; Military Preparedness 11.

6. Published by New Asia Press, October 1932. With a foreword dating from 1930. The work documents the knowledge of martial arts master Qiū Mínggāo (邱鳴皋) who at the time was heading the Yangzhou Martial Arts Institute. The author, Jīn Yīmíng, was director at the traditional arts museum in Nanjing at the time. A translation was done by Paul Brennan, who kindly made the original text and his translation available here.

7. Draeger & Smith; Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts. Kodansha USA, 1981. Page 60.

8. Shosoin no token or "Sword Blades in the Shōsō-in". Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 1974.

9. References to such swords appear in the Qīndìng xù wénxiàn tōng kǎo (欽定續文獻通考) and Míng huì diǎn (明會典). Thanks to 陳兆偉 for pointing these references out to me.

10. The use of the gǔnbèi extended from the Ming to Qing periods. Read more about their Ming use on the Great Ming Military Blog.

11. See Swords and sabres of the Ming Dynasty at Great Ming Military Blog.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.