Language: Indonesian

Source: Carl Alfred Bock, 1882.

Description

Mandau is the commonly used name for a type of sword from the island of Borneo. It is found for example in August Hardeland's Dajaksch-deutsches Wörterbuch of 1859.1 The term was popularized by adventurer Carl Alfred Bock.2

The word literally means "headhunter" and was mainly used by the Kayans.3 Another locally used name was parang ilang.4

They are most famously associated with the Dayak headhunters but were used by most peoples on the island. They served as weapons, machetes, and status symbols.

A typical mandau of the Kenyah people of central Borneo.

Notes

1. August Hardeland; Dajaksch-deutsches Wörterbuch. 1859. Page 338.

2. Carl Alfred Bock; Head-hunters of Borneo: a narrative of travel up the Mahakkam and down the Barito; also, Journeyings in Sumatra. London, S. Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington. 1882. Pages 191-193.

3. Sixt Wetzler (editor); Steel and Magic. Edged Weapons of the Malay Archipelago. Deutsches Klingen Museum Solingen, 2020. Pages 126-132. Described by Michael Marlow.

4. For mention of parang ilang see among others Ivor Hugh Norman Evans; Among primitive peoples in Borneo; a description of the lives, habits & customs of the piratical head-hunters of North Borneo, with an account of interesting objects of prehistoric antiquity discovered in the island. Seeley, Service & Co Limited, London 1922. Page 292.

Characteristics

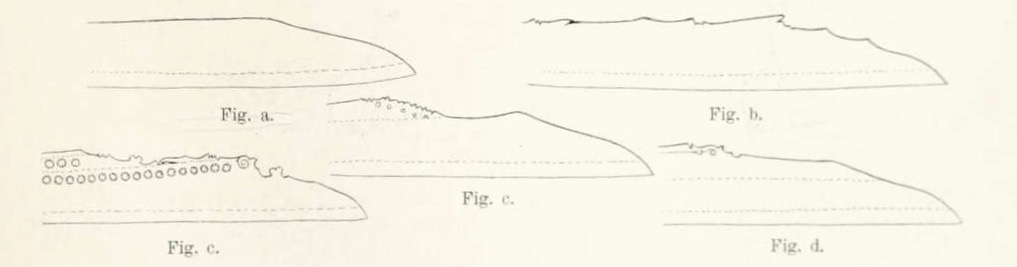

The most characteristic feature of the mandau is the blade's cross-section, being hollow ground on one side with a chisel edge to the other. In most cases the left side of the blade is hollow, but in some rare cases it was the other side, presumably for a left-handed swordsman.

This peculiar shape of the blade is said to render the parang more efficient in sinking into or through either limbs or wood, and is more easily withdrawn after a successful blow.1

Schematic drawing of a Mandau cross-section.

In profile the mandau tends to be fairly straight with only a moderate curve. The blade starts narrow at the base and widens towards the tip. The edge is longer than the back, with a sloped section towards the tip at the end.

Hilts are usually of carved deer antler or wood, usually with designs of aso (dog-dragon) and leeches. Hilts are often further adorned with tufts of human or animal hair. The grips are often covered with a very fine rattan braid. Where the blade meets the hilt is usually a generous application of kemalau, also known as gutta-percha, a natural thermoplastic latex made from the sap of the Palaquium gutta tree.

A mandau pommel. Here called parang, a generic word for sword.

From William Henry Furness; The home-life of Borneo head-hunters: its festivals and folk-lore. 1902.

The scabbards are made of carved wood held together with braided rattan. They usually carry an additional bark sheath with a small by-knife with a long handle. Often thought to be to clean out human skulls, but more frequently simply used for everyday chores like carving, and working rattan.

Such knives go by various names. They are called pisau raout in Bahasa, njoe in Bahau Dayak.2 Other terms in use were langgei puai and isaau.3

Notes

1. Charlses Hose, William McDougall, Alfred C. Haddon; The pagan tribes of Borneo; a description of their physical, moral and intellectual condition, with some discussion of their ethnic relations. London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd. Page 160.

2. Anton Willem Nieuwenhuis; In Centraal Borneo: reis van Pontianak naar Samarinda. E.J. Brill, Leyden. 1900. Page 361.

4. Donny Winardi. Personal communication.

Production, sub-types and decoration according to Tromp

Sometimes, it's handy to be Dutch, especially when it comes to Indonesian arms. S.W. Tromp, a resident of Kutai, Borneo, published some materials on mandau manufacture in the area.

In bepaalde takken van eigenlijk gezegde industrie vinden Dajaks anders dan bij uitzondering geen voldoende middelen van bestaan. Er zgn wel enkele plaatsen in Eoetei, waar men zich meer dan elders op het vervaardigen van „mandau" toelegt; zoo b. v. is ten dezen Djoehalang in de Oeloe Hahakam, in de nabijheid waarvan men zeer goed ijzererts vindt, nog al gerenommeerd, maar zelfs hier kan men niet zeggen dat de wapensmederij of ijzerfabrikatie in het algemeen van velen een hoofdbedrijf uitmaakt; trouwens de beste mandau's worden in Koetei ingevoerd van Poh Kedjin (zie boven).

S.W. Tromp; Een reis naar de bovenlanden van Koetei.

Tijdschrift voor Indische taal-, land-, en volkenkunde

Koninklijk Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen, 1853

My translation:

"In certain branches of actual industry, with few exceptions, Dayaks do not find sufficient means of subsistence. There are some places in Koetei where people focus more than elsewhere on the production of "mandau"; for example, Djoehalang in the Oeloe Hahakam, in the vicinity of which very good iron ore is found, is quite renowned, but even here it cannot be said that the weapons making or iron manufacturing, in general, is the main business of many; in fact the best mandaus are imported into Koetei from Poh Kedjin (see above)."

The following information is from his later article Mededeelingen omtrent mandau's of 1887:

Tromp noticed that the mandau of Kutai was characterized by having a straight back, while the back of the more northern Berau gently curves upwards. He also notes that within Kutai, two main types were made; a large and a short type:

-The shorter mandau was primarily used by the southern Tunjung, Bentian and Benua or "Southern Dayaks".

-A much larger and heavier type was used primarily by the Bahau, Kenyah, Kajan, Penhing and Punan Dayaks or "Central Dayaks" and the lowlands of Kutai.

The better blades were purchased from the Kenyah people of a village called Poh-Kedjin, in the mountains of central Borneo along the Kayan river. Price paid for a blade was 10 to 12 Dutch guilders. (About €135,- - €160,- today) If one wanted a very good blade, they would give it to a logger for a few years who would use it to clear jungle for rice paddies. If undamaged after a certain period, it would be ground to shape using stones, bulging on one side, hollow on the other. This work is very labor intensive and could cost up to 50 Dutch guilders. (About €675,- today.)

Nieuwenhuis, writing in 1900 sheds light on bladesmithing among the Bahau and explains why there is a need to carefully test the resulting blades:

Van de vaardigheid der Bahau-smeden en van de hoedanigheid der door hen gemaakte zwaarden heeft men zich lang een verkeerd denkbeeld gevormd. Eenig begrip van het onderscheid tusschen ijzer en staal bezitten zij niet; zij zien slechts, dat, wanneer het ijzer er op eene bepaalde wijze uitziet, het bruikbaar en anders onbruikbaar is. Hunne toebereiding van het ijzer geschiedt met houtskool, waarmede zij het ijzererts , dat men in de beken en riviertjes van den Zuidelijken Mahakam-oever in knolvorm vindt , uitsmelten; dan bepaalt het toeval, hoeveel kool er in het ijzer komt en dus wat voor soort van ijzer het wordt. De gelijkmatigheid in het verkregen stuk is even wisselvallig en het gebeurt niet zelden , dat een afgesmeed zwaard gedeeltelijk slecht blijkt te wezen en het geheel weer moet worden gebroken en omgesmeed. Is het grootendeels of gedeeltelijk staal en laat het zich harden , dan gebeurt dit ook zonder oordeel des onderscheids ; men heeft noch een juiste maat voor het gloeiend maken , noch gebruikt men eene andere vloeistof dan water van de gewone temperatuur. Daarom is het smeden van goede zwaarden eene zeer tijdroovende bezigheid en onder de als zoodanig afgeleverde blijft het een toeval, wanneer er een van goed homogeen staal is , dat naar den eisch gehard blijkt te wezen.

A.W. Nieuwenhuis; In Centraal Borneo. Reis van Pontianak naar Samarinda.

Maatschappij ter Bevordering van het Natuurkundig Onderzoek der Nederlandsche Koloniën, 1900

Page 272

My translation:

"People have long had an inaccurate impression of the skill of the Bahau smiths and of the quality of the swords they made. They have no understanding of the difference between iron and steel; they only see that when the iron looks a certain way, it is usable and otherwise unusable. Their preparation of iron is done with charcoal, with which they smelt the iron ore that is found in tuber form in the streams and rivers of the Southern Mahakam bank; then only chance determines how much carbon ends up in the iron, and therefore what type of iron it becomes. The uniformity of the resulting piece is equally variable, and it not infrequently happens that a forged sword turns out to be partially defective and the whole has to be broken and reforged again. If it is largely or partly steel and allows it to harden, then this also happens without discrimination; one has neither a proper measure for incandescence, nor does one use any other liquid than water of normal temperature. Therefore, forging good swords is a very time-consuming activity and among those delivered as such it remains a coincidence if there is one made of good homogeneous steel that appears to be hardened as required."

While these Kenyah mandau blades did not come pre-ground, they did come in one of a variety of general shapes;

Their names in the Long Way Dayak language;

A.) Leng / Monong

B.) Longna

C.) Lidjib

D.) Li-po-tong

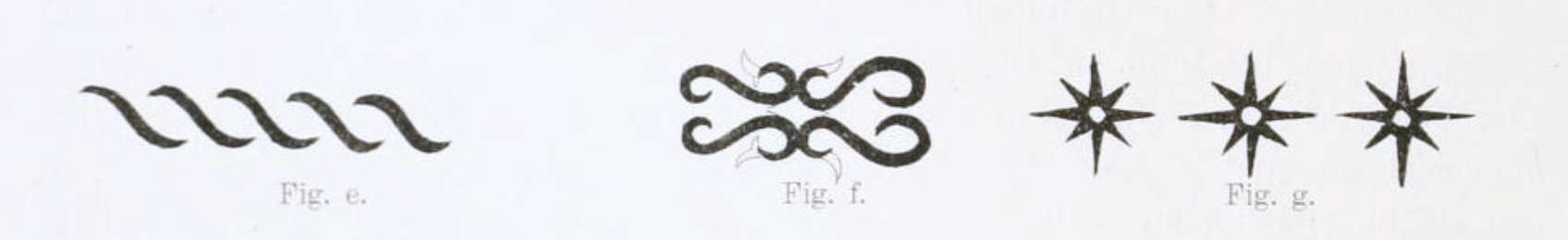

Decoration

The most common decoration are round pins that are either inlaid into the blade or go all the way through. They were said by some to represent each head taken with the sword, but Tromp, writing in 1887 doesn't believe it and gives good reason not to: First and foremost because some natives also said it was not the case. But also, because the blade has to be heated to red hot for each and every consecutive pin if not done in one go. Third, mandau with many plugs are offered for sale across the Dayak lands so anyone could purchase one. And lastly, some have so many of them that it is inconceivable that these all represent hunted heads.

E.) Mata djoh

F.) Mata kalong

G.) Tap-set-sien

Of the last one, anyone can use the center circle, but the radiant lines can only be used by royalty.

Blueing

Some mandau blades are adorned by blueing the cutting edge. This was done by cutting into the fresh stem of a kapok tree, and pulling the blade through the cut with each chop. It creates a beautiful blue edge that is retained for about six months.

Hilts

The hilts are called so-op and are generally made of a very hard wood or deer bone or antler.

H.) So-op kěnhong; Entirely smooth.

I.) So-op kombeh; Not deeply cut.

K.) So-op goanliklik; Deeply cut.

L.) So-op njong pěnjoh. (No explanation given.)

Older people often add a tuft of hair to their hilts, usually human hair.

Scabbards

The scabbard is made of two pieces of soft wood. Two main scabbard types are differentiated;

1. Sarong sěltoep (Kutainese) or sěgoen doengban / sěgoen sěnpot (Long Way). A piece of rattan covers where the cutting edge sits. Used primarily for presentation pieces because the construction gradually blunts the edge of the mandau.

2. An unnamed, common type that has visible bindings on the outside of the scabbard, called poesět-blanak. The amount of these relates to status of the wearer, often seen are three, sometimes four. Five were reserved only for royalty.

Attached to the scabbard is a těmpěsing, a sheath for the by-knife. Attached to the těmpěsing one can wear hair or feathers (often of the toekan), as long as one wants, but never shorter than the scabbard. This is only for the Sultan. If shorter, it is called běngat for hair or běnbol for feathers.

Also often attached to the těmpěsing are ornamentations of beads called loedang in Kutainese and těpěngah in Dayak. One pays about 25 guilders for a nice one. One can also attach one tiger tooth, but only the Sultan can have two.

Another ornamentation to the těmpěsing is black, white, and red goat hair applied in stages. Anyone can have these, as long as they follow the direction of the scabbard. Such ornamentation at right angles to the scabbard is called ěnding hělang is reserved for champions and people that Tromp calls měntěri's. Two of these ornamentations, in the direction of the scabbard but opposing each other are called njěloh and are bestowed as an honor by the Sultan. Two ornamentations of applied goat hair, both in the direction of the scabbard, are for the exclusive use of the Sultan.

Explanation to plate:

1-4. Mandau of the Sultan of Kutai

1. Blade

2. Scabbard, front

3. Scabbard, back

4. Edge side of scabbard showing the rattan

5. The by-knife

6. Wool string with beads, attached with a brass hook

7-8. Parts of a different mandau scabbard

9. Mandau hilt adorned with hair

Lastly, while writing in september 1887, Tromp notices that over a year ago the Sultan forbid the wearing of the mandau for anything but while laboring. Tromp sees this as a good thing because the people having them ever at the ready gave them a rough image. Also, he thought too much time and money was spent on mandau !

Notes

All the above information including the plates is from S.W. Tromp; Mededeelingen omtrent mandau's. Den Haag, 1887. Published in Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie, International Gesellschaft für Ethnographie; Rijksmuseum van Oudheden te Leiden, 1888. Volume 1, pages 22-26.

In period sources

"The principal weapon is the mandau, literally “head-hunter,” of which each Dyak has from four to six. These are placed in a rack hung against the wall in his room, the weapon being always kept out of its sheath with the blade greased to prevent rust. The blade -concave on one side, and convex on the other- is about twenty-one inches long, nearly straight, one and a half inches broad in the middle, and tapering towards the end to a sharp point.

It has only one cutting edge, the back being a quarter of an inch thick. The blade is made of steel or fine iron, which is abundant in Borneo. Although I have often seen the blade in the rough, in process of being sharpened and properly shaped, I have never seen either mine or smelting furnace, and could not ascertain where the raw material really came from.

The process of grinding and sharpening is very slow, and to polish and put a proper edge on a plain blade occupies more than a fortnight. Many of the blades are beautifully inlaid with brass along the sides near the back, while others have open scroll patterns cut right through the blade (see Plate 18, Fig. 3). How this work is done I could not ascertain as both Dyaks and Malays were very chary of giving any information, and very unwilling to show me any of their tools. Regular workshops do not seem to exist, each man being apparently, to a great extent at least, his own cutler.

The handle or hilt is generally made of deer^horn, sometimes of ironwood, and is highly ornamented with scrolls and ingenious and symmetrical designs of animals, trees, monsters, &c. The only instrument used for the purpose is a broad sharp-pointed knife -means which seem quite inadequate to the end attained, for many of these carvings would do credit to a skilled English workman. (Plate 18, Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

Plate 18

A thick rim of gutta-percha marks the point where the handle is fitted to the blade. Here are hung tassels of horse-hair, dyed various colours, or more often of human hair taken from victims.

The sheath is made of soft wood, the two sides being separately cut, and joined securely together at three or four points by coils of beautifully plaited rattan. The end of the sheath is guarded by an ivory ferule; and about two inches from its extremity depends a tassel of hair, the length of which increases according to the higher rank of the owner of the mandau.

On the under side of the sheath is a receptacle made of bark, carrying a small knife (see Plate 18, Fig. 2), the blade of which is three and a half inches, and the handle twelve inches, in length. This knife is used by the Dyak for severing the heads of the victims that fall to his mandau, and removing from them the fleshy parts; also for skinning animals killed in the chase; and in the more peaceful work of carving the ornaments which adorn his mandau, etc.

The sheath is carried by a belt made of very finely plaited rattan; the “buckle” or fastening consists of a loop at one end of the belt, through which is passed a piece of shell, or the upper mandible of the hornbill, or, as I saw among the Tring Dyaks, the kneecap of a human being, fastened at the other end of the belt." 1

-Carl Alfred Bock, 1882

Notes to period sources

1. Carl Alfred Bock; Head-hunters of Borneo: a narrative of travel up the Mahakkam and down the Barito; also, Journeyings in Sumatra. London, S. Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington. 1882. Pages 191-193.

Glossary

Aso, dog-dragon.

Běngat, short hair attached to the těmpěsing. Only for the Sultan.

Běnbol, short toekan feathers attached to the těmpěsing. Only for the Sultan.

Ěnding hělang a type of goat hair decoration on mandau scabbard, reserved for champions and měntěri's.

Gutta-percha, a natural thermoplastic latex made from the sap of the Palaquium gutta tree. Also known as kemalau.

Kemalau, also known as gutta-percha, a natural thermoplastic latex made from the sap of the Palaquium gutta tree.

Leng, a mandau point shape.

Lidjib, a mandau point shape.

Li-po-tong, a mandau point shape.

Loedang, Kutainese for bead decorations attached to mandau scabbard.

Longna, a mandau point shape.

Mata djoh, a type of inlaid decoration on mandau blades that consists of a series of S shapes.

Mata kalong, a type of inlaid decoration on mandau blades that consists of highly stylized dragon shapes.

Monong, a mandau point shape.

Njěloh a type of goat hair decoration on mandau scabbard, bestowed as an honor by the Sultan.

Parang ilang, alternative name for the mandau.

Pisau raout, literally "rattan knife", the by-knife carried in a sheath alongside the mandau scabbard.

Poesět-blanak, rattan bindings on mandau scabbards.

Sarong sěltoep (Kutainese) or sěgoen doengban / sěgoen sěnpot (Long Way). Scabbard where a piece of rattan covers where the cutting edge sits. Used primarily for presentation pieces because the construction gradually blunts the edge of the mandau.

Sěgoen doengban / sěgoen sěnpot, Long Way term for sarong sěltoep.

So-op, hilt of the mandau.

So-op goanliklik, deeply cut mandau hilt.

So-op kěnhong, entirely smooth mandau hilt.

So-op kombeh, not deeply cut mandau hilt.

So-op njong pěnjoh, a type of mandau hilt. (No explanation given.)

Tap-set-sien, a type of inlaid decoration on mandau blades that consists of blazing stars.

Těmpěsing, scabbard for the by-knife. Often made of palm bark.

Těpěngah, Dayak word for for bead decorations attached to mandau scabbard.

Further reading

Some fantastic swords from Borneo are featured in Sixt Wetzler (editor); Steel and Magic. Edged Weapons of the Malay Archipelago. Deutsches Klingen Museum Solingen, 2020. For mandau, see pages 126-132. Described by Michael Marlow.

For an excellent overview of Indonesian edged weapons typology with references to primary sources, see Albert van Zonneveld; Traditional Weapons of the Indonesian Archipelago. C. Zwartenkot Art Books, Leiden, 2001. For mandau, see pages 87 & 88.

Dr. H.H. Juynboll; Catalogus van 's Rijks Ethnographisch Museum. Deel 2: Borneo. 1910. Pages 202-247. A thorough description of a number of pieces in the Dutch ethnographic museum.

Dr. A.W. Nieuwenhuis; In Centraal Borneo. Reis van Pontianak naar Samarinda. Leiden, E.J. Brill, 1900. 2 volumes. Volume 1 page 223 described deer antler sword hilt production. Volume 2 page 366-269 describes sword production and decoration with accompanying plates.

Dr. Wilhelm Hein; Indonesische Schwertgriffe. Annalen des k.k. naturhistorischen Hofmuseums 14. 1899. Pages 317-358. A richly illustrated German language work on Indonesian hilts. Available online.