Introduction

A good sword needs to be capable of taking a keen edge in sharpening and keeping it intact during use. This requires a degree of hardness, but a sword cannot be all hard, or it would break like glass. Over the ages, swordsmiths of all cultures have come up with many good solutions to this problem.

The most important factor in creating a good sword is the heat treatment. This consists first of quenching, which is the rapid cooling of the steel, and annealing, which is re-heating to alleviate some of the stresses of the quenching. During quenching, steel with a higher carbon content will form more martensite crystals in a pearlite matrix, making this steel very hard and brittle. The visual aspect of this is the hamon line we see on Japanese swords. Lower carbon steel will not temper as hard, and will give the blade toughness and resilience.

By placing low and high-carbon steels in specific portions of the blade, one has more control over which parts harden and to what extent. This article will describe several methods by which the Japanese joined higher and lower carbon steels into their blades. Keep in mind that every type of steel would itself also be forge folded to drive out impurities, so each section you see would itself be layered but usually fairly homogenous in its carbon content.

The methods

Below is a list of the construction methods that are found in the literature, illustrated with a cross-section of the blade.

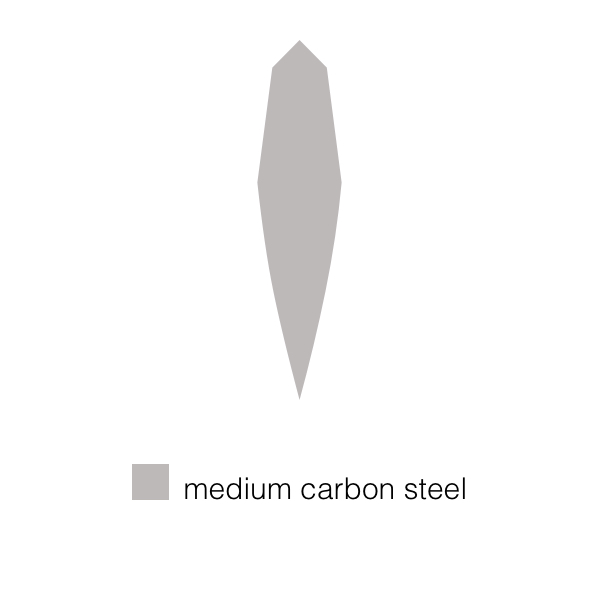

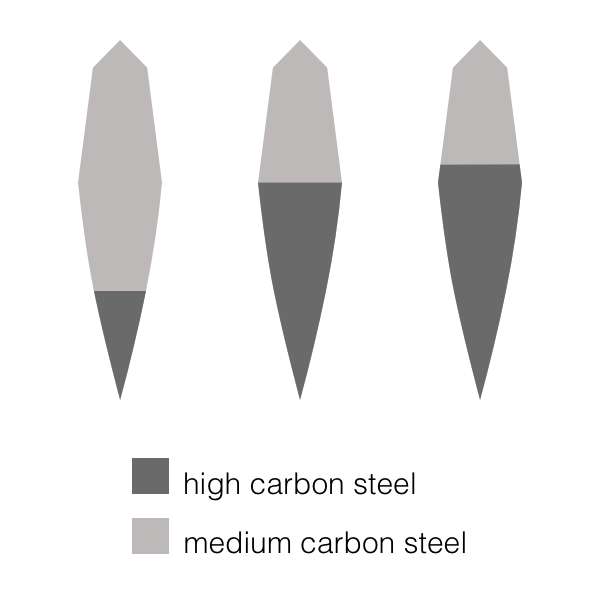

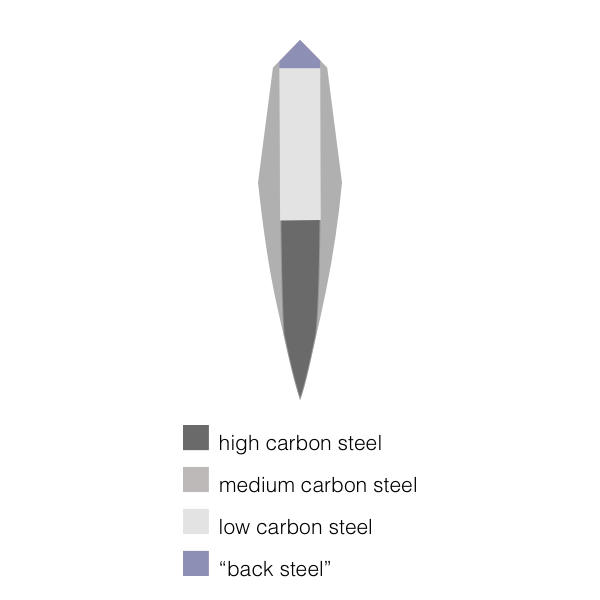

Some of the steels that are used in such constructions. In my illustrations, the higher carbon steels are a darker grey than the lower ones. By order of carbon content, here are the Japanese names of some of the steel types:

Hagane (刃鉄 / 刃金), "edge steel." High carbon steel.

Kawagane (皮鉄 / 皮金), “skin steel.” Medium carbon steel.

Munegane (棟鉄 / 棟金), "back steel". Lower to medium carbon steel.

Shingane (心鉄 / 心金), "core steel." Lower carbon steel or iron.

Notes

Markus Sesko; Encyclopedia of Japanese swords. Lulu Publishing. 2014. (Available for purchase here.)

Maru-gitae (丸鍛え)

In the most basic construction, a single type of medium to high-carbon steel is used. Differences between hardness in the edge and body of the steel come solely from the heat treatment applied on the finished blade.

This method was most common on all blades in early Kotō work but remained in use on shorter blades in all periods.

Some experts believe that if you use very good base steel and good hardening and annealing procedures, this method probably yields some of the best results. Many later methods with low carbon sections of the blade may have been primarily designed to save the expensive, top-quality steel without giving in too much on quality.

Notes

Markus Sesko; Encyclopedia of Japanese swords. Lulu Publishing. 2014. Page 280. (Available for purchase here.)

Hyoshigi-gitae (拍子木鍛え)

Hyoshigi are Japanese clappers that look like two beams of square cross-section. It refers to the start of this forging process where steels are laid out like beams and then forged together. How much hagane is used varies, see illustration.

Commonly seen in older Yamato school work. The Yamato school is the oldest of the five traditions of the Kotō period.

Notes

See the tsurikomi article by the Kashima sisters.

Wariha-gitae / wariba-gitea (割刃鍛え)

Somewhat similar to the hyoshigi construction above, with the difference that the edge steel is spliced in instead of just forged on.

There is also a method called gyaku kōbuse-gitae (逆甲伏せ鍛え) or "reversed kōbuse" that achieves pretty much the same result by wrapping the softer back around the edge, with the edge exposed.

Notes

Markus Sesko; Encyclopedia of Japanese swords. Lulu Publishing. 2014. Page 519. (Available for purchase here.)

Kōbuse-gitae (甲伏せ鍛え) and makuri-gitae (捲り鍛え)

These are basically two ways to achieve the same general result; a softer core wrapped in a high-carbon steel jacket. Kōbuse literally means "armor covered," and makuri means "rolling".

This is by far the most common construction method seen in antique Japanese swords. It is less labor-intensive than the more elaborate constructions below, yet it makes a fine sword with a hard, durable outside. An added advantage is that the high carbon steel jacket can form martensite crystals everywhere and thus works as an excellent canvas for the smith to create the most fantastic tempering effects in ha, hamon, and ji.

Commonly seen on the much coveted Bizen and Sōshu swords, schools both known and loved for spectacular heat treatment effects. In the case of Sōshu swords, the high carbon steel jacket itself would often consist of alternating layers with more and less carbon, which in quenching created lines with more or less nie particles in arrangements that resemble brushed sand called sunagashi (砂流し).

(This construction is also called Sōshū-gitae. Some Sōshū-gitae, however, may not have a soft core at all and so I don't list it here as a separate construction.)

Notes

See the tsurikomi article by the Kashima sisters. Also Markus Sesko; Encyclopedia of Japanese swords. Lulu Publishing. 2014. Pages 278 & 336. (Available for purchase here.)

Also see my glossary articles kōbuse and makuri.

Sanmai-gitae (三枚鍛え)

Literally "three-layer forging", this construction uses high carbon steel for core and edge, supported by tougher outer layers. Similar to the Chinese sānméi (三枚) construction.

An advantage of this construction is that the blade can bear a lot of polishing and still have core steel exposed at the edge, whereas with other constructions, softer core steel would at some point be exposed. A disadvantage is that an edge crack can run from edge to back.

Seen on swords by the Hasebe (長谷部) school of Yamashiro, active in the 14th-15th centuries, and the Gassan (月山) school of Settsu, active 19th to 20th centuries, and some Mino swords.

Notes

See the tsurikomi article by the Kashima sisters. Also Markus Sesko; Encyclopedia of Japanese swords. Lulu Publishing. 2014. Page 376. (Available for purchase here.)

Hon-sanmai-gitae (本三枚鍛え)

Similar to sanmai with the addition of a separate, softer core piece.

Notes

See the tsurikomi article by the Kashima sisters. Also Markus Sesko; Encyclopedia of Japanese swords. Lulu Publishing. 2014. Page 123. (Available for purchase here.)

Shihōzume-gitae (四方詰め鍛え)

Similar to the hon-sanmai above but with the addition of a separate section of so-called munegane (棟鉄 / 棟金) at the back.

Notes

See the tsurikomi article by the Kashima sisters. Also Markus Sesko; Encyclopedia of Japanese swords. Lulu Publishing. 2014. Page 390. (Available for purchase here.)

Jūgomai kōbuse-gitae (十五枚甲伏鍛え)

A special variation of kōbuse, probably invented by Ōmaru Kaboku around the 1660s. It is described in detail in Ōmura Kaboku's book Kentō Hihō (剣刀秘宝). He uses two types of core steel; shin-jitetsu (心地鉄) “core base steel” and shin-hatetsu (心刃鉄) “core edge steel”. He would wrap this construction in a layer of skin steel that he called tsurabuse-uwatetsu (面伏上鉄) “lying over surface steel”. The core base steel would be folded 15 times, hence the name.1

The construction was continued by his students, who like himself inscribed in on the tangs of the swords they made this way. Among them was Musashi Tarō Yasukuni who taught the method to Musashimaru Yoshiteru, who in turn passed it on to Suishinshi Masahide, who was to become a grandmaster swordsmith, and founder of the Shinshinto sword-making period.

Notes

See Markus Sesko; Encyclopedia of Japanese swords. Lulu Publishing. 2014. Page 399-400. (Available for purchase here.)